This is a special edition of the blog in which I am honored to host a full paper that has been authored by Detective Cindy Murphy of the Madison, Wisconsin Police Department. Cindy Murphy is a lethal forensicator and if you make the decision to engage in technology related crime, I highly recommend avoiding doing so in Madison, Wisconsin. Cindy will find you and you will go to jail. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

In addition to being a very sharp computer forensic examiner, she does cutting edge research in the area of mobile device forensics. For example, she has developed the fraternal clone method for CDMA phones which has been published in the Journal of Small Scale Digital Forensics.

You can find a PDF version of this paper over at Jesse Kornblum’s website.

Cellular Phone Evidence Data Extraction and Documentation

By Detective Cindy Murphy

Developing Process For The Examination

of Cellular Phone Evidence

Recently, digital forensic examiners have seen a remarkable increase in requests to examine data from cellular phones. The examination of cellular phones and the extraction of data from the same present challenges for forensic examiners:

· The numbers of phones examined over time using a variety of tools and techniques may make it difficult for an examiner to recall the examination of a particular cell phone.

· There is an immense variety of cellular phones on the market, encompassing a array of proprietary operating systems and embedded file systems, applications, services, and peripherals.

· Cellular phones are designed to communicate with the phone network and other networks via Bluetooth, infrared and wireless (WiFi) networking. To best preserve the data on the phone it is necessary to isolate the phone from surrounding networks, which may not always be possible.

· Cellular phones employ many internal, removable and online data storage capabilities. In most cases, it is necessary to apply more than one tool in order to extract and document the desired data from the cellular phone and its storage media. In certain cases, the tools used to process cellular phones may report conflicting or erroneous information, thus, it is critical to verify the accuracy of data from cellular phones.

· While the amount of data stored by phones is still small when compared to the storage capacity of computers, the storage capacity of these devices continues to grow.

· The types of data cellular phones contain and the way they are being used are constantly evolving. With the popularity of smart phones, it is no longer sufficient to document only the phonebook, call history, text messages, photos, calendar entries, notes and media storage areas. The data from an ever-growing number of installed applications should be documented as these applications contain a wealth of information such as passwords, GPS locations and browsing history.

· The reasons for the extraction of data from cellular phones may be as varied as the techniques used to process them. Cellular phone data is often desired for intelligence purposes and the ability to process phones in the field is attractive. Sometimes though, only certain data is needed. In other cases full extraction of the embedded file system and the physical memory is necessary for a full forensic examination and potential recovery of deleted data.

Because of the above factors, the development of guidelines and processes for the extraction and documentation of data from cellular phones is extremely important. What follows is an overview of process considerations for the extraction and documentation of cell phone data.

Cellular Phone Evidence Extraction Process

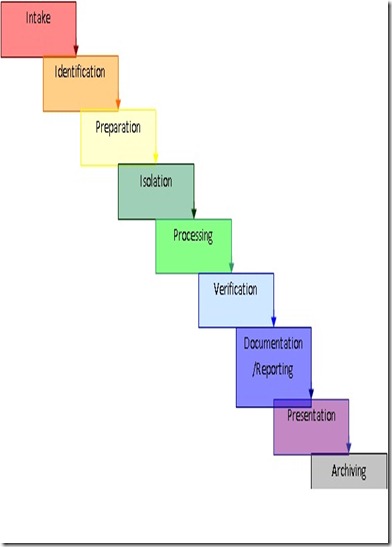

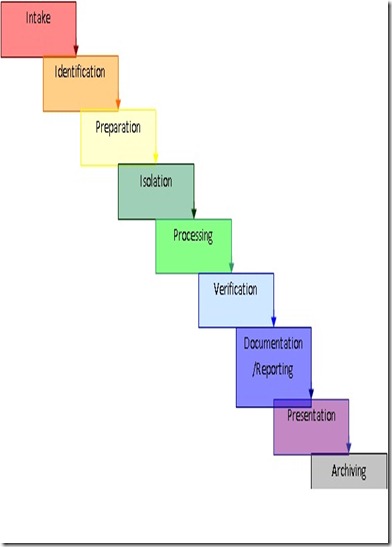

Figure 1: Evidence Extraction Process

Evidence Intake PHASE

The evidence intake phase involves the procedure by which requests for examinations are handled. The evidence intake phase generally entails request forms and intake paperwork to document chain of custody, ownership information, and the type of incident the phone was involved in and outlines general information regarding the type of data the requester is seeking to have extracted or documented from the phone.

A critical aspect at this phase of the examination is the development of specific objectives for each examination. This not only serves to document the examiner’s goals, but also assists in the triage of examinations and begins the documentation of the examination process for each individual phone examined. This information allows the examiner to triage cellular phones.

Identification PHASE

For every examination, the examiner should identify the following:

· The legal authority to examine the phone

· The goals of the examination

· The make, model and identifying information for the cellular phone itself

· Removable & external data storage

· Other sources of potential evidence

Legal Authority:

Case law surrounding the search of data contained within cellular phones is in a nearly constant state of flux. It is imperative that the examiner determines and documents what legal authority exists for the search of the cellular phone, as well as what limitations are placed on the search of the phone prior to the examination of the device:

- If the cellular phone is being searched pursuant to a warrant, the examiner should be mindful of confining the search to the limitations of the warrant.

- If the cellular phone is being searched pursuant to consent, any possible limitations of the consent (such as consent to examine the call history only) and should determine whether consent is still valid prior to examining the phone.

- In cases where the phone is being searched incident to arrest, the examiner needs to be particularly cautious, as current case law in this area is particularly problematic and in a state of constant change.

Particular questions as to the legal authority to search a cellular phone should be directed to a knowledgeable prosecutor or legal advisor in the examiner’s local area. (Mislan, Casey & Kessler 2010)

The Goal of the Examination:

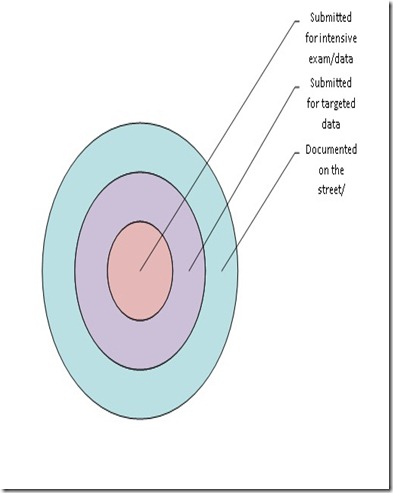

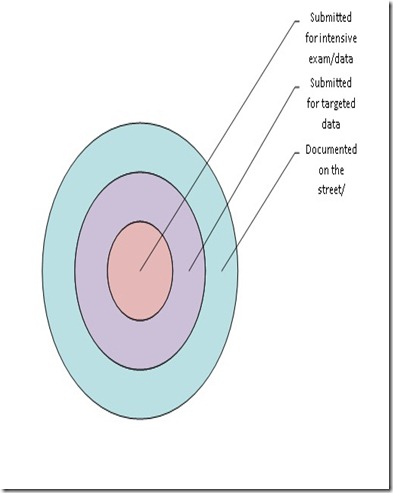

While the general process used to examine any given cellular phone should be as consistent as possible, the goal of the examination for each phone may be significantly different. It is unlikely that any given forensics lab has the capability nor the capacity to examine every cellular phone that contains data of evidentiary value in every kind of case. For this reason, it can be useful to identify what level of examination is appropriate for any given cellular phone.

The first of two main considerations is who will be responsible for the process of documenting the data. The second main consideration is how in depth the examination needs to be. Of those phones that are submitted to the lab for examination, there will be differences in the goals of each examination based upon the facts and circumstances of the particular case.

In some cases evidence from cellular phones may be documented in the field either by hand or photographically. For example, in the interest of returning a victim’s main communication lifeline while still documenting information of evidentiary value, or in the case of documenting evidence in a misdemeanor or minor offense, field documentation would be a reasonable alternative to seizing the device. In other cases, it may be sufficient to have an officer or analyst with basic training in the examination of cellular phones perform a quick dump of cellular phone data in the field, specifically for intelligence purposes using commercially available tools designed for this purpose.

A smaller subset of cellular phones may be submitted for examination with the goal of targeted data extraction of data that has evidentiary value. Specifically targeted data, such as pictures, videos, call history, text messages, or other specific data may be significant to the investigation while other stored data is irrelevant. . It also might be the case that only a certain subset of the data can be examined due to legal restrictions. In any event, limiting the scope of the exam will likely make extraction and documentation of the data less time consuming.

The goal of the exam may alternatively include an attempt to recover deleted data from the memory of the phone. This is only possible if a tool is available for a particular phone that can extract data at a physical level (See levels detailed at the end of this section). If such a tool is available, then the examination will involve traditional computer forensic methods such as data carving and hex decoding, and examination process may be a time consuming and technically involved endeavor, as deeper levels of examination necessitate a more technically complex and time consuming process.

Figure 2: Goal of the Exam

The goal of the exam can make a significant difference in what tools and techniques are used to examine the phone. Time and effort spent initially on identification of the goal of the exam with the lead investigator in the case can lead to increased efficiency in the examination process.

These types of realities should be addressed in training, and the triage process related to the initial submission of cellular phones for examination should based upon the individual circumstances and severity of the case.

The Make, Model and Identifying Information for the Cellular Phone:

As part of the examination of any cellular phone, the identifying information for the phone itself should be documented. This enables the examiner not only to identify a particular phone at a later time, but also assists in the determination about what tools might work with the phone as most cellular phone forensic tools provide lists of supported phones based on the make and model of the phone. For all phones, the manufacturer, model number, carrier and the current phone number associated with the cellular phone should be identified and documented.

Depending upon the cellular phone technology involved, additional identifying information should be documented, if available, as follows:

CDMA cellular phones:

The Electronic Serial Number (ESN) is located under the battery of the cellular phone. This is a unique 32 bit number assigned to each mobile phone on the network. The ESN may be listed in decimal (11 digits) and/or hexadecimal (8 hex digits). The examiner should be aware that the hex version of the ESN is not a direct numeric conversion of the decimal value. An ESN converter can be found at http://www.elfqrin.com/esndhconv.html.

The Mobile Equipment ID (MEID), also found under the battery cover, is a 56 bit number which replaced the ESN due to the limited number of 32 bit ESN numbers. The MEID is listed in hex, where the first byte is a regional code, next three bytes are a manufacturer code, and remaining three bytes are a manufacturer-assigned serial number. CDMA phones do not generally contain a Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card, but some newer hybrid phones contain dual CDMA and GSM technology and can be used on either CDMA or GSM networks. Inside these dual technology phones is located a slot for a SIM card. The identifying information under the battery of these phones may list an IMEI number in addition to the ESN/MEID number.

CDMA phones also have two other identifying numbers, namely, the Mobile Identification Number (MIN) and Mobile Directory Number (MDN). The MIN is a carrier-assigned, carrier-unique 24-bit (10-digit) telephone number. When a call is placed, the phone sends the ESN and MIN to the local tower. The MDN is the globally-unique telephone number of the phone. Prior to Wireless Number Portability, the MIN and MDN were the same but in today's environment, the customer can keep their phone number (MDN) even if they change carriers.

GSM cellular phones:

The International Mobile Equipment Identifier (IMEI) is a unique 15-digit number that identifies a GSM cellular phone handset on its network. This number is generally found under the battery of the cellular phone. The first 8 digits are a Type Allocation Code (TAC) and the next 6 digits are the Device Serial Number (DSN). The final digit is a check digit, usually set to 0.

On a GSM phone, there will be at least a Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) card slot which is also generally located under the battery. The SIM card may be branded with the name of the network to which the SIM is registered. Also located on the SIM card is the Integrated Circuit Card Identification (ICCID), which is an 18 to 20 digit number (10 bytes) that uniquely identifies each SIM card. The ICCID number is tied to the International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) which is typically a 15-digit number (56 bits) consisting of three parts including the Mobile Country Code (MCC; 3 digits), Mobile Network Code (MNC; 3 digits in the U.S. and Canada, and 2 digits elsewhere), and Mobile Station Identification Number (MSIN; 9 digits in the U.S. and Canada, and 10 digits elsewhere) which are stored electronically within the SIM. The IMSI can be obtained either through analysis of the SIM or from the carrier.

The Mobile Station International Subscriber Directory Number (MSISDN) is the phone's 15-digit, globally unique number. The MSISDN follows the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Recommendation E.164 telephone numbering plan, composed of a 1-3 digit country code, followed by a country-specific number. In North America, the first digit is a 1, followed by a 3-digit area code.

iDen cellular phones:

iDen cellular phones contain an International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) that identifies an iDen cellular phone on its network. This number is generally found under the battery of the cellular phone. iDen cellular phones also contain SIM cards, with the identifying information described above, though they are based on different technology than GSM SIM cards and are not compatible with GSM cellular phones.

Unique to iDen cellular phones is the Direct Connect Number (DCN) which is also known as the MOTOTalk ID, Radio-Private ID or iDen Number. The DCN is the identifying number used to communicate directly device-to-device with other iDen cellular phones. This number consists of a series of numbers formatted as ###*###*##### where the first three digits are the Area ID (region of the home carrier’s network), the next three digits are the Network ID (specific iDen carrier) and the last five digits are a subscriber identification number which sometimes corresponds to the last five of the cellular phone number. (Punja, & Mislan, 2008)

Removable /External Data Storage:

Many cellular phones currently on the market include the ability to store data to a removable storage device such as a Trans Flash Micro SD memory expansion card. In the event that such a card is installed in a cellular phone that is submitted for examination, the card should be removed by the examiner and processed using traditional digital forensics techniques. The processing of data storage cards using cellular phone forensic tools while the card remains installed within the phone may result in the alteration of date and time stamp data for files located on the data card.

Additionally, cellular phones may allow for the external storage of data within network based storage areas accessible to the phone’s user by computer. Accessing this data, which is stored on the cellular phone service provider’s network, may require further legal authority and is generally beyond the scope of the examination of a cellular phone handset. However, the potential existence of network based data storage should be taken into account by the examiner.

Many feature phones and smart phones are also designed to sync with a user’s computer to facilitate access to and transfer of data to and from the cellular phone. Full backups of the data from a phone may be found on the phone owner’s computer. The potential for the existence of these alternative storage areas should be considered by the examiner as additional sources of data originating from cellular phones.

Other Potential Evidence Collection:

Prior to beginning examination of a cellular phone, consideration should be given to whether or not other evidence collection issues exist. Cellular phones may be good sources of DNA, fingerprint or other biological evidence. Collection of DNA, biological and fingerprint evidence should be accomplished prior to the examination of the cellular phone to avoid contamination issues.

Preparation PHASE

Within the Identification phase of the process, the examiner has already engaged in significant preparation for the examination of the phone. However, the preparation phase involves specific research the regarding the particular phone to be examined, the appropriate tools to be used during the examination and preparation of the examination machine to ensure that all of the necessary equipment, cables, software and drivers are in place for the examination.

Once the make and model of the phone have been identified, the examiner can then research the specific phone to determine what available tools are capable of extracting the desired data from the phone. Resources such as phonescoop.com and mobileforensicscentral.com can be invaluable in identifying information about cellular phones and what tools will work to extract and document the data from specific phones. The SEARCH toolbar (available as a free download from www.search.org) contains additional and regularly updated resources for cellular phone examinations.

Appropriate Tools:

The tools that are appropriate for the examination of a cellular phone will be determined by factors such as the goal of the examination, the type of cellular phone to be examined and the presence of any external storage capabilities.

A matrix such as the one shown below of the tools available to the examiner, and what general technology of phones (GSM, CDMA, iDEN, SIM Card) they are compatible to be used with in an examination may also be helpful.

| | CDMA | GSM | iDen | SIM | Logical Dump | Physical Dump |

| BitPim | X | | | | X | |

| Data Pilot Secure View 2 | X | X | | | | |

| Paraben Device Seizure | X | X | | X | X | |

| SIMCon | | | | X | | |

| iDen Media Manager | | | X | | | |

| Manufacturer / Other | X | X | X | X | | |

| Cellebrite | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| CellDEK | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Oxygen Forensic Suite | X | X | | X | | |

| XRY / XACT | X | X | X | X | X | X |

Figure 3: Cellular Phone tool matrix (Kessler, 2008)

Cellular Phone Tool Leveling System:

When identifying the appropriate tools for the analysis of cellular phones, a useful paradigm is the Cell Phone Tool Leveling System. (Brothers, 2009) The tool leveling system is designed to categorize mobile phone and GPS forensic analysis tools by the depth to which they are capable of accessing data on a given device. As you move up the pyramid (generally):

· Methods get more “forensically sound”

· Tools get more expensive

· Methods get more technical

· Longer Analysis times

· More training required

· More invasive

Figure 4: Cellular Phone Tool Leveling Pyramid – (Brothers 2009)

1. Manual Analysis – physical analysis of the phone involving manual manipulation of the keyboard and photographic documentation of data displayed on the screen.

2. Logical Analysis - Connect data cable to the handset and extract data using AT, BREW, etc. commands in client/server architecture.

3. Physical Analysis (Hex Dump) - Push a boot loader into phone, dump the memory from phone and analyze the resulting memory dump.

4. Physical Analysis (Chip-Off) - Remove memory from the device and read in either second phone or EEprom reader.

5. Physical Analysis (Micro Read) - Use an electron microscope to view state of memory.

In general, examinations gather more detailed information and take more time as one advances through the levels.

Other resources that should not be overlooked are cellular phone manufacturer’s and cellular phone carrier’s websites. They can contain links to electronic versions of manuals for almost every make and model of phone as well as cable and phone driver downloads. Manufacturers will also sometimes provide free software designed for users to access and synchronize the data on their phones with their computers. While these tools are not designed specifically for extraction and documentation of evidence, they may be useful when other tools do not work. Caution should be used when utilizing these tools, as they are generally designed to access and write data back to a cellular phone.

Isolation PHASE

Cellular phones are by design intended to communicate via cellular phone networks. They are also sometimes capable of connecting to each other and to other networks via Bluetooth, infrared and wireless (WiFi) network capabilities. For this reason, isolation of the phone from these communication sources is important prior to examination. Isolation of the phone prevents the addition of new data to the phone through incoming calls and text messages as well as the potential destruction of data through a kill signal or accidental overwriting of existing data as new calls and text messages come in.

Isolation also prevents overreaching of the legal authority of warrant or consent that covers data on the phone. If the phone is isolated from the network, the examiner cannot accidently access voicemail, email, Internet browsing history or other data that may be stored on the service provider’s network rather than on the phone itself.

Isolation of a cellular phone in the field can be accomplished through the use of Faraday bags or radio frequency shielding cloths which are specifically designed for this purpose. Other available items such as arson cans or several layers of tinfoil may also be used to isolate some cellular phones. One problem with these isolation methods however is that once they’re employed, it is difficult or impossible to work with the phone as you can’t see through them or work with the phone’s keypad through them. Faraday tents, rooms, and enclosures exist, but are cost prohibitive.

Additionally, some laboratories within the US federal government may use signal jamming devices to curtail radio signals from being sent or received for a given area. The use of such devices is illegal for many organizations and their use should only be implemented after verifying the legality of the use of such devices for a given organization. Additional information about the FCC exceptions can be found at www.fcc.org.

Another viable option is to wrap the cellular phone in radio frequency shielding cloth and to then place the phone into Airplane mode (Also known as Standalone, Radio Off, Standby or Phone Off Mode). Instructions for how to place a phone into Airplane mode can be found in the manufacturer’s user manual for the particular make and model of cellular phone.

Unfortunately, not all phones have an Airplane mode, and sometimes even the most seemingly foolproof isolation methods can fail. Even if a cellular phone is successfully isolated from all networks, user data can still be affected if automatic functions are set to occur, such as alarms or appointment announcements. If these situations arise the examiner should document their attempts to isolate the phone and whether any incoming calls, text messages or other data transmissions occur during the course of the examination.

Processing PHASE

Once the phone has been isolated from the cell phone and other communication networks, the actual processing of the phone may begin. The appropriate tools to achieve the goal of the examination have been identified in the steps described previously, and they can now ideally be used to extract the desired data from the phone.

Accessing data stored on these cards through use or processing of the cellular phone may alter data on the data storage card thus any installed data storage/memory cards should be removed from the cellular phone and processed separately using traditional computer forensics methods to ensure that date and time information for files stored on the data storage/memory card are not altered during the examination. Similarly, SIM cards should be processed separately from the cellular phone they are installed in to preserve the integrity of the data contained on the SIM card.

Consideration should be given to the order of the software and hardware tools used during the examination of the cellular phone. There are advantages to consistency in order of tools used during examination of a cellular phone. This consistency may help the examiner to remember the order of tools used in the examination at a later time. Also, depending on the circumstances, it may make sense to use more intrusive tools first or last during the course of the examination depending upon the goals of the exam. For example, if the goal is to extract deleted information from the physical memory of the phone, starting the examination with a physical dump of the memory (if tools for this function are available) would make more sense than extracting individual files or the file system of the phone.

Verification PHASE

After processing the phone, it is imperative that the examiner engages in some sort of verification of the accuracy of the data extracted from the phone. Unfortunately, it is not unusual for cellular phone tools to erroneously or incompletely report data or to have different tools report conflicting information. Verification of extracted data can be accomplished in several ways.

Comparison of Extracted Data to the Handset

Comparison of the extracted data to the handset simply means checking to be sure the data which was extracted from the cellular phone matches the data displayed by the phone itself. This is the only authoritative way to ensure that the tools are reporting the phone information correctly.

Use of More than One Tool, Compare Results

Another way to ensure the accuracy of extracted data is to use more than one tool to extract data from the cellular phone and to cross verify the results by comparing the data reported from tool to tool. If there are inconsistencies, the examiner should use other means to verify the accuracy of the data extracted from the phone. Even if two tools report information consistently, verification via manual inspection of the handset is authoritative.

Use of Hash Values

If file system extraction is supported, traditional forensic tools can be used for verification of extracted data in several ways. The forensic examiner can extract the file system of the cell phone initially, and then hash the extracted files. Any individually extracted files can then be hashed and checked against the originals to verify the integrity of individual files.

Alternatively, the examiner could extract the file system of the cell phone initially, perform the examination and then extract the file system of the phone a second time. The two file system extractions can then be hashed and the hash values compared to see what data on the phone, if any, has been altered during the examination process. Any changed files should then be examined to determine if they are system files or user files to potentially determine the reason for the changes to the files. (Murphy, 2009) It should be noted that hashing only validates the data as it exists after it has left the phone. Cases where the data extraction process actually modifies data have been documented in other papers. (Dankar, Ayers & Mislan 2009)

In some cases, a combination of verification techniques may be employed to validate the integrity of the data extracted from the phone.

Documentation & reporting PHASE

Documentation of the examination should occur throughout the process in the form of contemporaneous notes regarding what was done during the examination. Examination worksheets can be helpful in the examination process to ensure that basic information is recorded.

The examiner’s notes and documentation should include information such as:

· The date and time the examination was started

· The physical condition of the phone

· Pictures of the phone and individual components (e.g., SIM card and memory expansion card) and the label with identifying information

· The status of the phone when received (off or on)

· Make, model, and identifying information

· Tools were used during the examination

· What data was documented during the examination

Most cellular phone tools include reporting functions, but these may not be sufficient for documentation needs. At times, the cellular phone tools may report inaccurate information such as the wrong ESN, MIN / MDN numbers, model, or erroneous date and time data, and so care must be taken to document the correct information after data verification. For law enforcement purposes, the process used extract data from the phone, the kinds of data extracted and documented and any pertinent findings should be accurately documented in reports. Even if the examiner is successful in extracting the desired data using available tools, additional documentation of the information through photographs may be useful, especially for court presentation purposes.

Presentation PHASE

Consideration should be given throughout the examination as to how the information extracted and documented can clearly be presented to another investigator, prosecutor and to a court. In many cases, the receiver may prefer to have the extracted data in both paper and electronic format so that call history or other data can be sorted or imported into other software for further analysis.

The investigator may also want to provide reference information regarding the source of date and time information, EXIF data extracted from images or other data formats, in order that recipients of the data are better able to understand the information.

For court purposes, pictures or video of the data as it existed on the cellular phone may be useful or compelling as exhibits. Extracted text messages may be great evidence, but pictures of the same text messages may be more familiar and visually compelling to a jury.

It is often very useful to present a series of pictures of text messages and call history logs in chronological order via a simple PowerPoint® presentation so that the progression of communications is shown clearly to the audience, whether the audience is an investigator, prosecutor, or jury. This is especially effective if there are a number of cellular phones involved in a case.

Archiving PHASE

Preservation of the data extracted and documented from the cellular phone is an important part of the overall process. It is necessary to retain the data in a useable format for the ongoing court process, future reference, and for record keeping requirements. Some cases may endure for many years before a final resolution, and most jurisdictions require that data be retained for varying lengths of time for the purposes of appeals.

Due to the proprietary nature of the various tools on the market for the extraction and documentation of cell phone data, consideration should be given to the ability to access saved data at a later date. If possible, store data in both proprietary and non-proprietary formats on standard media so that the data can be accessed later even in the event that the original software tool is no longer available. It may also be a good practice to retain a copy of the tool itself to facilitate the viewing of the data at a later date.

Conclusion

With the growing demand for examination of cellular phones and mobile devices, a need has also developed for the development of process guidelines for the examination of these devices. While the specific details of the examination of each device may differ, the adoption of consistent and well documented examination processes will assist the examiner in ensuring that the evidence extracted from each phone is well documented and that the results are repeatable and defensible in court. The information in this document is intended to be used as a guide for forensic examiners and digital investigators in the development of processes that fit the needs of their workplace.

The author wishes to thank the following individuals for their thoughtful and insightful additions as well as their assistance in reviewing and editing the content of this document:

· Richard Ayers –National Institute of Standards in Technology

· Sam Brothers – US Customs and Border Protection

· Richard Gilleland – Sacramento Police Department

· Michael Harrington –

· Eric Huber – A Fistful of Dongles

· Gary Kessler – Gary Kessler Associates

· Andrew Muir – Intern, Madison Police Department

· Tim O’Shea – US Attorney’s Office, Western District of Wisconsin

Bibliography

Brothers, S. (2009). How Cell Phone "Forensic" Tools Actually Work - Proposed Leveling System. Mobile Forensics World 2009. Chicago, Illinois

Ayers, R., Dankar, A. & Mislan, R. (2009). Hashing Techniques for Mobile Device Forensics. Small Scale Digital Device Forensics Journal , 1-6.

Kessler, G. (2010). Cell Phone Analysis: Technology, Tools, and Processes. Mobile Forensics World. Chicago: Purdue University.

Mislan, R.P., Casey, E., & Kessler, G.C. (2010). The Growing Need for On-Scene Triage of Mobile Devices. Digital Investigation, 6(3-4), 112-124

Punja, S & Mislan, R. (2008). Mobile Device Analysis. Small Scale Digital Device Forensics Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1 , 2-4.

Murphy, C. (2009). The Fraternal Clone Method for CDMA Cell Phones. Small Scale Digital Device Forensics Journal , 4-5.